Recommendations for Legal Assistance

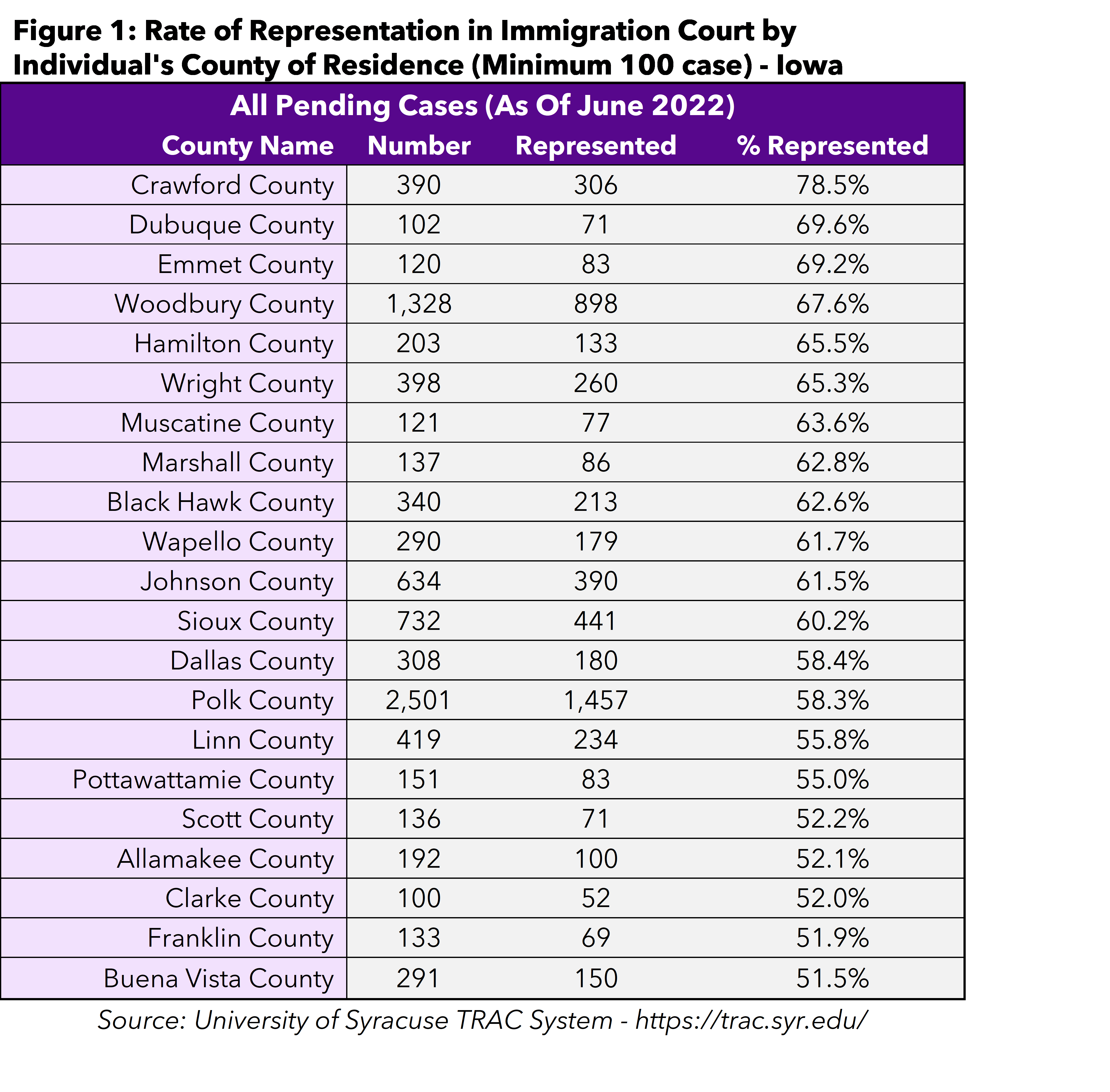

One of the valuable assets in this region is the presence of attorneys who can represent individuals in immigration court proceedings. Both through immigration lawyers at organizations like Catholic Charities and Path of Hope and through dedicated private attorneys who represent immigrants in legal proceedings, the legal advocacy in the region provides an important service to local immigrants. As Figure 1 on the next page shows, of counties in Iowa with at least 100 immigration court cases currently pending (as of June 2022), Dubuque County had the second highest rate of representation at 69.6%. This doesn’t necessarily show the full need for immigration legal services (due to immigrants not pursuing cases because of a lack of representation), but does give a sense of the amount of legal representation provided compared to other counties in Iowa. This support is extremely valuable for ensuring that immigrant community members are able to be represented in immigration court, or at the least to receive a consultation about their case.

Yet this level of support can be precarious. In rural communities a sudden influx of new immigrants with court cases can overwhelm the available representation, and the loss of even one attorney (due to moving, illness, etc.) can leave a community understaffed. In addition, due to the importance of legal activities that take place outside of immigration court (such as submitting I-94 forms or applying for citizenship), there is almost always a need for additional legal capacity for immigrants. Because of this, the region should place a priority in ensuring that there is sufficient access to quality legal services for immigrants. If such services become scarce, it is very possible that immigrants will face worse outcomes in court, or that immigrants will rely on unethical attorneys or those without adequate training in immigration law for their legal needs.

Models to consider:

- A nonprofit organization called Vecina connects volunteer attorneys to immigration court cases, providing the attorneys with additional mentoring and training on immigration law as well. This increases the capacity of pro-bono legal services for immigrants while ensuring that lawyers have some training in immigration law and avoid doing anything that may harm their client.

- The New York Immigrant Family Unit Project is working to provide a publicly funded lawyer to every detained or incarcerated immigrant in the state. Immigrants are generally not provided with a public defender for immigration court cases or deportation hearings.

As detailed above, the amount of paperwork involved in navigating the immigration system is significant and can act as a major challenge for immigrant families and a disincentive for pursuing necessary help and services. The same is true of the fees required for immigrant applications. In addition, making mistakes or omissions on a form can lead to that application being rejected.[1] Being able to provide support for immigrant families looking to make legal applications can make those applications both more feasible and more successful.

Both volunteers and staff at local organizations provide support with filling out forms. Volunteers from within immigrant communities and the larger pool of immigrant activists frequently play an important role in helping prepare documentation for immigration submissions due to the unmet need that exists within the region. While their efforts should be celebrated, at times the informal nature of their work means that the process can be inefficient (because they are dealing with new paperwork they have not seen before) and may possibly lead to errors or mistakes. A better option will usually be a more formal volunteer program (where volunteers can be given training or guidance on how to fill out forms), or paid staff and social workers assisting with documents. Having dedicated resources who are compensated for their work available to help with paperwork can be a major benefit for immigrant communities. For more information on navigators, see the Navigators section.

An additional need identified during the course of this research is around fees for family members who have been detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Individuals in detention face significant costs, such as fees for telephone calls. Maintaining communication between a detained individual and their family can be very important, but many immigrants are unable to afford these calls, especially when they are isolated from their community.[2] During the Covid-19 pandemic there were several efforts by local volunteers and organizations in Dubuque to raise money to help with costs and fees for immigrant families with a member in detention.

Being able to help with fee payments, either by fully covering them or reducing the amount, can have a major impact on the well-being of immigrant families. In this region this has both been accomplished by organizations utilizing grant funding to cover costs, and by fundraising to create a pool of money that can be accessed by immigrant families. Communities should consider organizing and growing a pool of available funding to help low-income immigrants cover fees.

Models to consider:

- Crescent Community Health Center employs both social workers and community health workers who can work with members of immigrant communities on issues like I-94 completions or passport renewals. Crescent also utilizes grant money to help offset the costs of these filings for immigrant populations.

- The Presentation Lantern Center has a fund that is replenished annually through donations that is aimed at helping cover fee costs for citizenship applications or other immigration-related applications.

- The Mission Asset Fund in San Francisco provides 0% interest loans for immigrant application fees like citizenship, green cards, or DACA. This provides immigrants with financial support and allows them to rebuild credit history as they repay the loan.

This recommendation also appears as Recommendation 5 under Case Management

Upon arriving in Iowa, many unaccompanied minors move forward with their immigration court case by applying for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS). This status provides the minor with a legal residency status in the U.S. and opens a pathway to applying for a green card and eventually citizenship. As part of applying for SIJS, the minor also becomes involved in a juvenile court proceeding that makes determinations that are important for SIJS. As part of this process, the juvenile court will also appoint a guardian for the minor to help ensure that the child’s needs are being met. Guardians can play an important role in helping unaccompanied minors access services and navigate unfamiliar systems.

However, because there is not a formally established system for identifying guardians, this can often cause issues. It is generally the responsibility of the minor and their advocates to identify a person willing to be a guardian. This often results in the minor’s attorney, a nonprofit staff person, or a volunteer soliciting help from people they know in order to secure a guardian.

What is Guardianship

Guardianship in SIJS cases is not always well understood, partly because the term “guardian” often means different things in different situations. In this case, the guardian’s role is to make sure that the minor’s well-being is being addressed and to report back to the court on any issues. The guardian does not have any financial responsibility for the child, nor does the child need to live with the guardian (though there have been instances where this has happened). The guardian’s job is to try to help figure out solutions for financial, housing, and other issues the minor might face, not to take care of those issues directly. So, if the unaccompanied minor accidentally damaged school property and needed to pay the school back, the guardian would be expected to help figure out a solution but would not have to cover the payment themselves. Anyone interested in becoming a guardian or learning more should speak with a qualified legal professional for more precise information.

This can lead to two issues. The first is that the minor and their advocates are unable to find an acceptable guardian before the minor ages out of the juvenile court system, thereby undermining their ability to apply for SIJS. In Iowa, guardianship must be established before the minor turns 18, and judges may be unwilling to grant guardianship if the minor is getting close to that age. If it takes a long time to find an appropriate guardian for the minor, it may pose a significant problem for their immigration court case. Informal systems based on personal networks may draw from a smaller pool of potential guardians.

The second issue is that this informal system of nonprofit staff/volunteers requesting help from their acquaintances sometimes leads to under-prepared guardians. These guardians may not adequately understand what guardianship entails and may be less committed to being a guardian, but instead may agree to the position out of necessity or as a favor to the person making the request. In some instances, individuals have been pressed to serve as guardian to multiple minors. Having guardians who are not fully committed to being guardians and who do not fully understand what being a guardian entails is a disservice to both the guardian and to the minor.

A solution proposed by service providers in the community is to create a more formal system where potential guardians can submit their names to a website hosted by a local organization. This website would provide information on what being a guardian entails and other important considerations, and would allow potential guardians to submit their name and contact information. This would add them to a list that could be accessed by immigration attorneys looking for a guardian for the unaccompanied minor they are representing. Such a system could also include:

- A background check to help ensure that potential guardians are appropriately screened;

- Testimonials to show the experiences of others who have served as guardians;

- Training programs, support groups, and other resources to help better support guardians in their new role; and

- Other services aimed to help the guardian or minor.

Such a system would provide a better process for referring people who are interested in being a guardian, helping to increase the pool of available guardians. It would also help ensure that potential guardians understand what they are signing up for and would reduce the pressure on nonprofit staff and volunteers to always seek out new guardians whenever one is needed. In addition, creating trainings and resources for guardians would improve the help they provide to minors as well as connecting with local social service organizations.

Models to consider:

- In Dubuque, the Multicultural Family Center (MFC) has been in conversations with Catholic Charities, the Community Foundation, and other advocates about hosting a guardian website. The language and content for the website would be developed by immigration attorneys and other support organizations, while the MFC would conduct background checks and hold the list of potential guardians. Immigrant advocates could then refer potential guardians to the website in order to gain more information and to submit their information. The MFC could also then offer services and opportunities both to the guardians and to the unaccompanied minors.

- The guardian list would only be accessible to immigration attorneys representing a minor seeking SIJS to help protect the privacy of those on the list.

- After multiple discussions with statewide organizations and advocacy groups, this research has not identified another website serving this role within Iowa. It could be a model to be used by other Iowa communities.

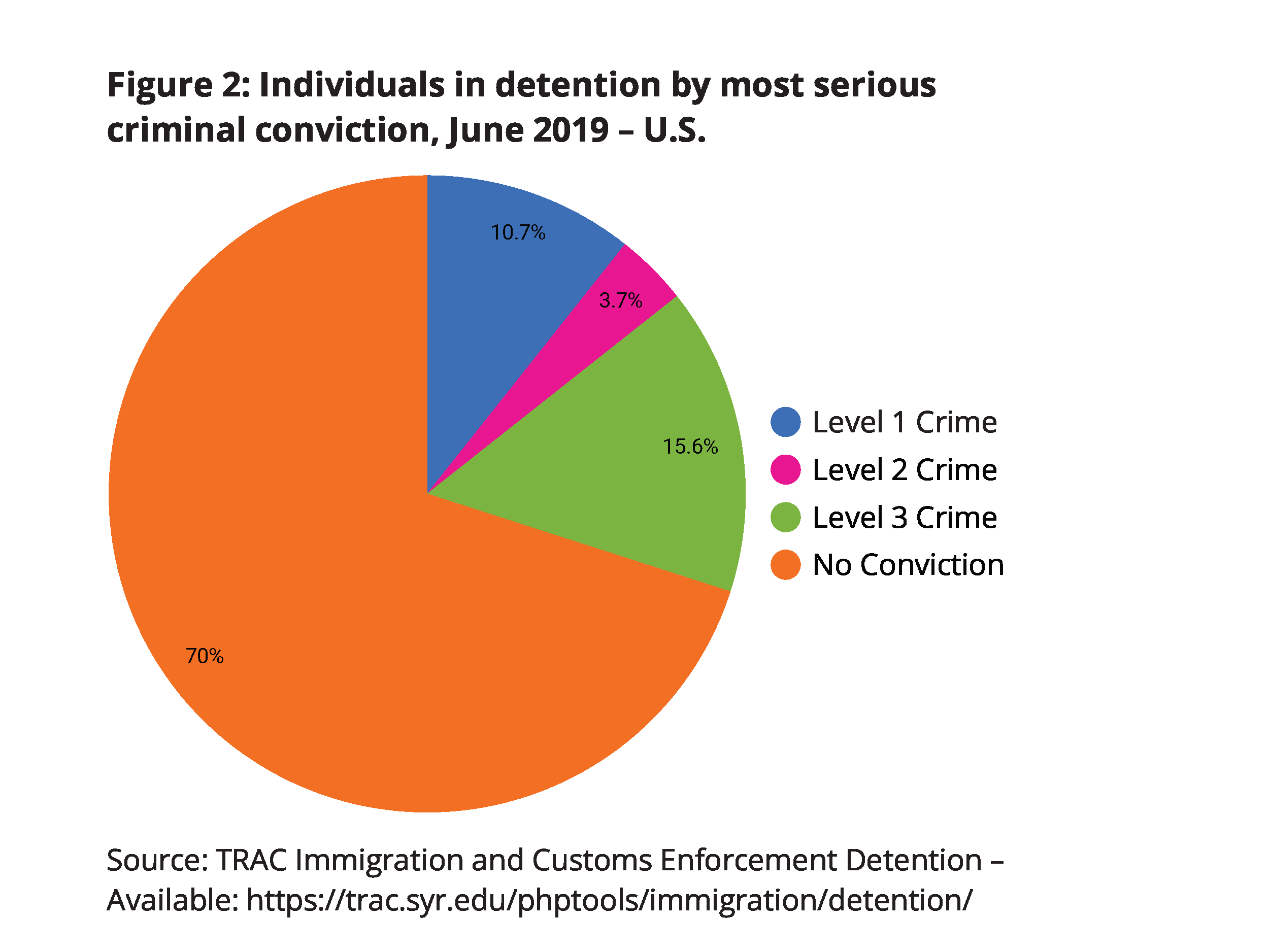

One of the common misconceptions about immigrant populations is that they are frequently responsible for increases in crime. A 2020 study found that immigrants (both undocumented and documented) were much less likely to be arrested for violent crimes, drug offenses, and property crimes than the general population.[3] This agrees with earlier studies on arrest rates of immigrants[4] as well as evidence that halting refugee resettlement[5] and increasing deportation[6] does not reduce property or violent crime rates. The most recent data from the University of Syracuse Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) database shows that a majority (70%) of individuals in immigrant detention in the summer of 2019 had not been convicted of a crime, and approximately 10.7% (or less than 6,000 nationwide) were designated as having a serious criminal conviction on their record.[7]

Yet a deficit of trust between immigrant populations and law enforcement may result in challenges that can impact a community. If immigrant populations are unwilling to speak with law enforcement, it could prevent them from providing information about other crimes. A lack of familiarity with local laws and miscommunication with law enforcement can also lead to some immigrants getting into avoidable legal trouble. In interviews several law enforcement personnel expressed a desire to improve communication with immigrant populations and explain common issues in order to reduce these types of problems.

There have also been instances within Dubuque County of law enforcement officials targeting or even seeking to intimidate immigrant communities. This kind of activity, even if it does not directly lead to arrests, can have a chilling effect on immigrants of all immigration statuses. Fear of increased police presence can undermine participation in social services and other programming, and may create a significant setback to efforts to build connections between immigrant populations and the larger community. In smaller and rural communities, even the actions of a single law enforcement official can have a major impact on a community’s relationship with its immigrant populations.

For these reasons improving the rapport and communication channels between immigrant communities and law enforcement can have significant benefits for the community as a whole. Potential options for programming include:

- Hosting information sessions for immigrant communities about common legal and public safety issues.

- Hosting listening sessions where immigrants can provide feedback to law enforcement about questions and concerns.

- While these sessions may focus on specific immigrant communities at different times, they should be made available to as wide an audience as possible (especially regarding authorization status) and should be held repeatedly and consistently to increase immigrant trust in the process.

- Establishing an immigrant advisory group to help provide input and direction to law enforcement bodies, as well as key points of contact within the community.

- Developing, with the assistance of members of immigrant communities, a clear and publicly visible protocol for how to use city and/or county resources when required to assist federal immigration authorities. Outlining policies can be an effective way to build additional trust with immigrant communities while reducing the potential for miscommunication.

- Adopting clear rules for when and how local officers can inquire into immigration status. This can give better direction to officers about how to use their discretion to ask about immigration status and can increase trust with immigrant communities.

Models to consider:

- In Iowa, the police department in Storm Lake has had success in conducting outreach to immigrant populations and building trusted channels of communication.

- The Immigrant Legal Resource Center put together a series of recommendations for Texas law enforcement offices designed to help improve policies and practices when working with immigrant populations.

- The National Immigration Forum’s program titled Bibles, Badges and Businesses for Immigration Reform engages with law enforcement leaders (as well as business and religious leaders) around issues concerning immigration and immigration reform.

One common misperception about immigration is that the immigration court system is a separate and independent court system like other U.S. courts, such as district courts where criminal charges are filed or U.S. Tax Court. Instead, immigration courts are part of the executive branch and the Department of Justice, serving under the Attorney General instead as part of the judicial branch. This has raised several concerns regarding how well immigration courts are able to effectively provide justice to immigrants. Such concerns include:

- Their placement under the executive branch can make them highly susceptible to political influence, with court decisions changing dramatically depending on who is the Attorney General. The American Bar Association has stated that, “Our current immigration court system cannot meet the standards to which justice demands.”[8]

- This system leads to dramatic disparities in the outcome of immigration court cases based on where the court is located and who is serving as a judge. [9]

- Legal representation is not guaranteed, and therefore whether an immigrant is able to obtain an immigration attorney to represent them in court has a significant impact on whether the immigrant can secure a successful outcome.[10]

- Legal standards for immigration judges are significantly different for judges in other court systems. For example, immigration judges are not required to have previous experience with immigration law.[11]

These and other concerns have led many advocates to push for the U.S. to change the immigrant court system to an independent system within the judicial branch of the government. Such a change would have an immense impact on local immigrants who are participating in the immigration court system, could reduce the expenses associated with immigration court (such as finding representation for immigrants), and would allow immigrants and immigrant support organizations to have a greater degree of confidence in court outcomes. In addition to advocacy, highlighting the current state of the immigration court system may help the general public better understand the barriers facing recent arrivals.

The argument to reform the immigration court system is highlighted in a 2019 report from the American Bar Association that states, “In light of the fundamentally changed nature of the threat to the immigration court system, the overall conclusion of this Update Report… is that the current system is irredeemably dysfunctional and on the brink of collapse, and that the only way to resolve the serious system issues within the immigration court system is through transferring the immigration court functions to a newly-created Article I court.”

One additional barrier facing many immigrants is needing to obtain a valid photo ID to access services. Photo IDs can be necessary for everything from qualifying for government programs to applying for utility services to receiving medical care. They can be especially important when working with law enforcement agencies and emergency services. But for many immigrants, obtaining valid photo ID can be challenging. Regulations and requirements in Iowa can make it difficult to obtain a driver’s license. This is certainly true for undocumented immigrants or those still waiting for their immigration court case, but can also be true for documented immigrants as well. For example, Marshallese residents who need to replace their I-94 form are unable to get a driver’s license until it is replaced. Given the difficulties residents have faced receiving an updated I-94, this can limit those individuals’ ability to obtain a valid photo ID (for more on I-94s, see the informational box in the Legal Assistance section of the Immigration Community Assessment Implementation Guide).

Several communities have worked to resolve this problem by issuing community-based photo IDs. These IDs are not a replacement for a driver’s license but can provide residents access to services and resources from which they otherwise might be excluded. There are many models of ID cards (see “Models to Consider” below), but all generally involve local agencies, businesses, and other organizations agreeing to utilize the ID cards as acceptable forms of identification for services. Community-based ID cards can also often be useful for other populations that may struggle to obtain valid photo ID, including elderly people, formerly incarcerated individuals, and people experiencing homelessness. Experience from other community-based ID programs shows that it is best to develop the cards to be useful for as wide a population as possible. This not only makes them more ubiquitous and more widely accepted, but can help avoid any stigma that cards might be “only for immigrants” or “only for the homeless.”

A community-based ID card could be a valuable addition for Dubuque and for other communities in the region. With a broad enough coalition of government departments, nonprofit organizations, and businesses supporting the cards, it could provide real value to immigrant groups and to entities like law enforcement and emergency services. There are a number of different models for these type of community-based ID card systems (several of which are located below), and a further analysis and discussion of these systems would be necessary to identify which would best meet local needs.

Models to consider:

- The FaithAction ID program is run by FaithAction International House across several states, including the Central Iowa Community ID Card Program in Story County and Marshall County, Iowa. The program is focused primarily on immigrants with limited legal status. This program is run by a nonprofit organization in close cooperation with local churches and law enforcement agencies.

- The Johnson County Community ID card is a card issued by the local government in Johnson County, Iowa. While it has many similarities to the Central Iowa program, a key difference is that the card is administered by the County Auditor’s office.

- In Texas, San Antonio and Houston use “Enhanced Library Cards” as community-based ID cards. The ID cards include the individuals photograph, address, and date of birth. Basing the card out of the local library system creates several advantages, including connecting the card to an important public resource, utilizing an existing infrastructure for ID cards, and helping avoid stigma surrounding the ID cards.

- https://guides.mysapl.org/enhancedlibrarycard

- The following links go to two videos regarding the San Antonio library card in English[12] and Spanish.[13]

[1] For example, see “Insider alert: No more room for error in visa applications?” Boundless Immigration. 27 November 2018. Available at: https://www.boundless.com/blog/insider-alert-no-room-error-visa-applications/#:~:text=USCIS%20announced%20a%20new%20policy,effect%20on%20September%2011%2C%202018.

[2] Najmabadi, Shannon. “Detained migrant parents have to pay to call their family members. Some can’t afford to.” The Texas Tribune. 3 July 2018. Available at: https://www.texastribune.org/2018/07/03/separated-migrant-families-charged-phone-calls-ice/

[3] Moyer, Melinda Wenner. “Undocumented immigrants are half as likely to be arrested for violent crimes as U.S.-born citizens.” Scientific American. 7 December 2020. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/undocumented-immigrants-are-half-as-likely-to-be-arrested-for-violent-crimes-as-u-s-born-citizens/

[4] Nowrasteh, Alex. “Illegal immigrants and crime – Accessing the evidence.” Cato Institute. 4 March 2019. Available at: https://www.cato.org/blog/illegal-immigrants-crime-assessing-evidence

[5] Masterson, Daniel, and Vasil Yasenov. “Does Halting Refugee Resettlement Reduce Crime? Evidence from the US Refugee Ban.” American Political Science Review, vol. 115, no. 3, 2021, pp. 1066–1073., doi:10.1017/S0003055421000150. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/does-halting-refugee-resettlement-reduce-crime-evidence-from-the-us-refugee-ban/E111764FC700841C5E5FD3FAA2A6BE8C

[6] Flagg, Anna. “Deportations reduce crime? That’s not what the evidence shows.” The New York Times. 23 September 2019. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/23/upshot/deportations-crime-study.html

[7] “Decline in ICE detainees with criminal records could shape agency’s response to Covid-19 pandemic.” Syracuse University TRAC Immigration System. 3 April 2020. Available at: https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/601/

[8] “ABA urges Congress to create separate immigration courts.” American Bar Association. July 2019. Available at: https://www.americanbar.org/news/abanews/aba-news-archives/2019/07/aba-urges-congress-to-create/

[9]“2019 Update Report, Volume 2 – Reforming the immigration system: Proposals to promote independence, fairness, efficiency, and professionalism.” American Bar Association Commission on Immigration. March 2019. Pg. 64 (UD 2-5). Available at: https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/commission_on_immigration/2019_reforming_the_immigration_system_volume_2.pdf

[10] Markowitz, Peter, et al. “Accessing justice: The availability and adequacy of counsel in immigration proceedings.” New York Immigrant Representation Study. December 2011. Page 3. Available at: https://justicecorps.org/app/uploads/2020/06/New-York-Immigrant-Representation-Study-I-NYIRS-Steering-Committee-1.pdf

[11] Rappaport, Nolan. “How many of our immigration judges are amateurs at immigration law?” The Hill. 23 November 2020. Available at: https://thehill.com/opinion/immigration/527104-how-many-of-our-immigration-judges-are-amateurs-at-immigration-law/

[12] Video available at: https://youtu.be/JLmbxF4nsPg

[13] Video available at: https://youtu.be/n1ki8CPJUwM

To return to the section on Issues Facing Immigrant Communities, click here. To explore this section more deeply, use the following links:

- For Case Management, click here

- For Education and Youth Support, click here

- For Health, click here

- For Housing, click here

- For Legal Assistance, click here

- For Translation and Interpretation, click here

- For Workforce and Employment, click here

To read a discussion regarding Ongoing Collective Work on Immigration, click here

For a discussion of Building Connections with Immigrant Communities, click here

For a list of Priority Recommendations, click here

To return to the Welcome Page, click here